Specialized Grant Writing and Funding Strategy

Beyond strong metrics, an innovative funding strategy including well thought out programs offer the best chance for funding.

The acquisition of grant funding is a critical component of financial stability for non-profit organizations, research institutions, and mission-driven entities. However, grant acquisition is not merely an administrative task; it is a strategic discipline known as grantsmanship. Grantsmanship involves managing the entire life cycle of a funding opportunity, beginning long before the proposal submission and extending far beyond the award date. Securing financial awards requires a professional, highly analytical, and meticulously compliant approach.

Funder Alignment and Program Design

Conducting the Authoritative Needs Assessment: Data, Evidence, and Quantification

The Needs or Problem Statement is arguably the most fundamental component of the proposal, establishing the justification for the entire project. This section must rigorously analyze the existing situation using the best available data. An authoritative assessment requires relying exclusively on hard data, not assumptions or undocumented assertions.

The data used must be relevant and specific to the proposal’s context. Professional grantsmanship dictates using comparative statistics and citing documented research sources whenever possible to quantify the situation. One of the most common reasons for rejection is a vague statement of need or a problem description that lacks quantified evidence. Furthermore, the scope of the problem identified must logically align with the scope of the proposed project. For example, presenting a problem of general, national scope while proposing a limited local intervention will lead reviewers to question the project’s feasibility and impact. The inclusion of documented, well-cited data serves as a primary credibility builder, signaling to the funder that the organization possesses the capacity for rigorous analysis and will manage the resources with similar diligence.

Designing a Fundable Project: The Power of Program Planning

Before the grant application is drafted, resources must be dedicated to solid program and project design. This foundational work involves assessing community needs, determining realistic goals, developing a viable strategy, and defining measurable benchmarks for success.

Defining Measurable Success: Goals and SMART Objectives

Objectives describe the anticipated, measurable accomplishments relative to the identified need. High-quality proposals utilize the S.M.A.R.T. framework to ensure objectives are Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. Measurable objectives are not just rhetorical flourishes; they establish the metrics for the Evaluation Plan and serve as an accountability contract between the grantee and the funder. If an objective is vague (e.g., “increase community awareness”), the funder cannot reliably track success, thereby increasing the risk associated with the investment. By employing the SMART framework, the objective becomes testable and directly informs the methodology, demonstrating a comprehensive, low-risk design.

Methodology and Rationale

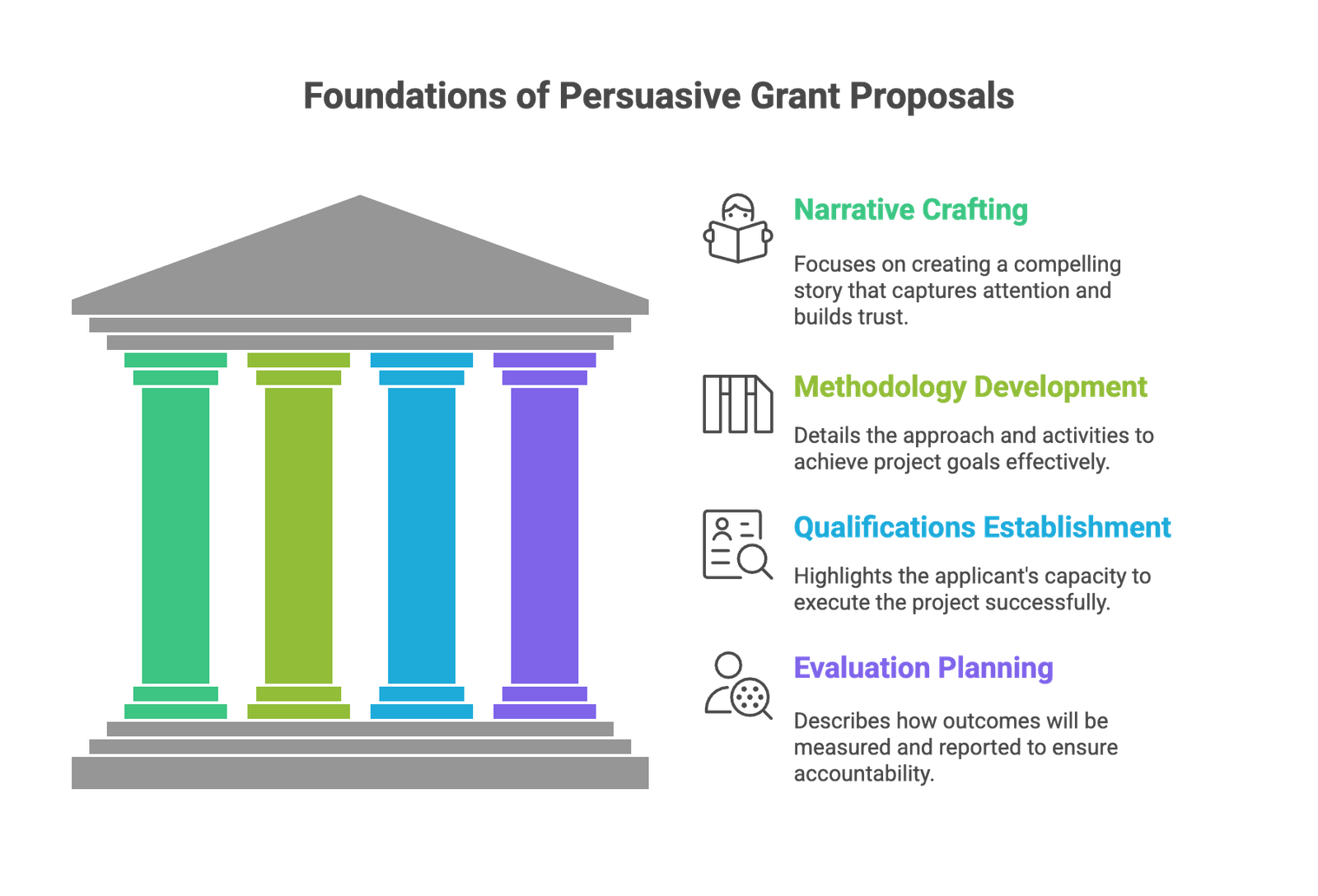

The Methodology section details the approach and specific activities designed to achieve the SMART objectives. This section must clearly outline the intended scope of work, expected outcomes, the activities involved, and descriptions of key personnel functions. Crucially, the methodology must be supported by a clear Rationale. This rationale should cite academic literature or established best practices to justify the chosen approach, lending immediate credibility to the proposed intervention. A detailed Project Timeline should accompany the methodology, visually painting the project flow, including start and end dates, schedules of activities, and projected outcomes or milestones.

Risk Management in the Application Phase: Addressing Common Rejection Pitfalls

Even projects with immense merit are rejected due to failures in execution and adherence to application protocol. A core function of professional grantsmanship is mitigating these common failures before submission.

Top reasons for proposal rejection include submitting to the wrong funding agency, failing to meet the submission deadline, poor writing quality, and, most critically, non-adherence to the funder’s guidelines regarding content, format, or length. Funders often refuse to read past the point where an applicant departs from the rules, regardless of the project’s intrinsic value.

Strategic Misalignment is Fatal. Submitting a proposal that is generic or fails to align explicitly with the funder’s mission, values, or strategic priorities is a primary reason for rejection. Reviewers prioritize proposals that clearly advance their mission. Furthermore, the presence of mechanical defects, such as excessive errors or carelessness in formatting, suggests that the applicant may lack the discipline required for successful project execution and post-award accountability.

Compliance with funder guidelines serves as the initial screening mechanism. To optimize the review process, proposals must be organized with clear subheadings that correspond directly to the funder’s evaluation criteria. This streamlines the reviewer’s scoring process, demonstrates responsiveness to the funder’s expectations, and significantly increases the proposal’s competitive edge during initial application intake.