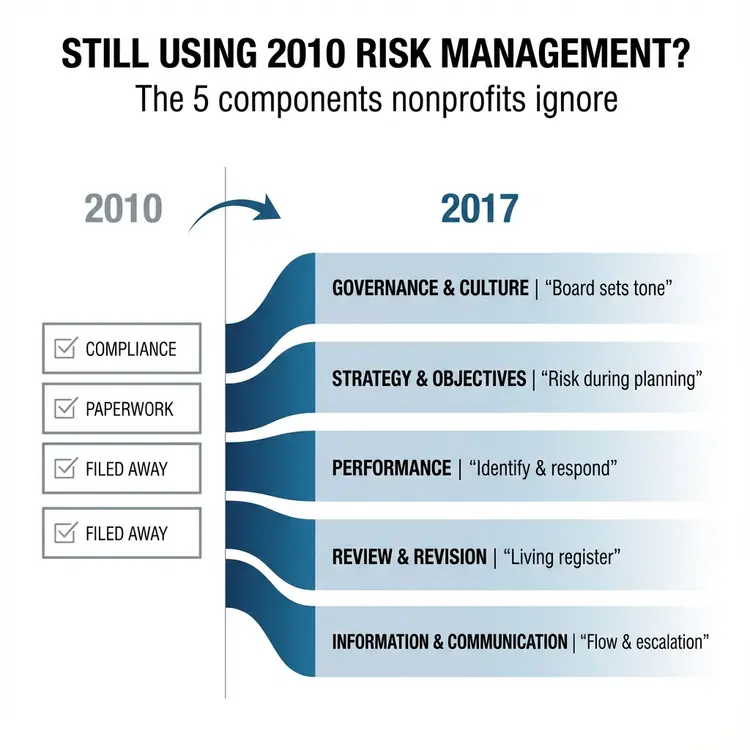

I spent years watching nonprofit leaders treat enterprise risk management like a compliance checkbox. Fill out the forms. File them away. Check the box for the board.

Then something changed in 2017.

The Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) released an updated Enterprise Risk Management framework that fundamentally repositioned how organizations should think about risk. The title itself told the story: “Enterprise Risk Management—Integrating with Strategy and Performance.”

This wasn’t about better compliance. This was about making risk management a strategic function that drives decisions, not documents them after the fact.

Yet most nonprofits still operate like it’s 2010.

The Problem: Risk Management as Paperwork

Before 2017, COSO’s own research revealed a troubling gap. Only 28% of organizations believed their ERM implementation was systematic, robust, and regularly reported to their board.

The rest? They had risk registers collecting dust.

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly in nonprofit organizations. A comprehensive risk assessment gets presented to the executive team with clear data and mitigation strategies. It gets shelved because it doesn’t align with their funding targets or mission priorities.

The real issue isn’t identifying risks. The real issue is getting leadership to act on them.

That’s the turning point the 2017 COSO framework addresses.

The Five Components That Change Everything

The updated framework consists of 20 principles organized into five interrelated components. These aren’t theoretical constructs. They’re operational tools designed for organizations of all sizes, from community nonprofits to major institutions.

1. Governance and Culture

This component establishes the foundation. Your board sets the tone for risk oversight. Your executive team defines risk appetite. Your organizational culture determines whether people report problems or hide them.

I once worked with a nonprofit where the finance leader had a reputation for removing anyone who delivered “bad news.” The result? A risk register filled with minuscule risks all labeled as high impact and high likelihood.

When everything is marked critical, nothing is actually prioritized.

I created a rubric that clearly defined likelihood and impact specifically for that organization’s financial context. Through several conversations, we rebuilt a risk register that actually guided decisions.

Governance isn’t about having policies. It’s about creating an environment where honest risk assessment is rewarded, not punished.

2. Strategy and Objective-Setting

This is where the 2017 framework breaks from traditional compliance thinking. Risk management doesn’t happen after you set strategy. It happens during strategy development.

You evaluate risks in the context of your strategic objectives. You consider risk appetite before committing to major initiatives. You align your risk tolerance with your mission priorities.

For nonprofits, this means asking: Does this program expansion align with our risk capacity? Can we sustain this funding model if our largest donor exits? What operational risks does this new partnership introduce?

Strategy without risk integration is just wishful thinking.

3. Performance

The performance component addresses how you identify, assess, and respond to risks that affect your objectives.

This is where most nonprofits focus their limited energy. They identify risks. They create heat maps. They categorize threats into financial, operational, technological, legal, regulatory, and strategic buckets.

But identification without response is useless.

When deciding how to respond to a specific risk, I use a systematic process:

Transfer: Can someone else bear this burden? Is there insurance, a contract structure, or a partnership that shifts responsibility? Is the cost of transfer less than the potential loss?

Avoid: Can we eliminate the risk entirely? Is the potential impact unacceptable? Does avoiding this risk mean abandoning a core objective?

Mitigate: Can we reduce the likelihood or impact to an acceptable level? What controls or processes would work? Does the cost of mitigation justify the risk reduction?

Accept: Are we willing to live with the consequences? Is this risk within our appetite? Do we have a contingency plan if it materializes?

Each question leads to the next. Each answer requires honest assessment of resources, priorities, and organizational capacity.

4. Review and Revision

Risk environments change. Your understanding of threats evolves. New vulnerabilities emerge.

A risk register that gets reviewed annually at a board meeting is already outdated.

I’ve found that living risk registers share common structural elements:

• Clear categorization by risk type (strategic, operational, financial, compliance, cyber)

• Specific ownership assigned to empowered individuals who can act

• Direct links to action plans with measurable indicators

• Visual dashboards that show status at a glance

• Defined escalation triggers that prompt immediate attention

• Integration with regular management meetings, not just annual presentations

But the real difference? A board member who makes risk management a priority and demands updated information.

Without executive accountability, even the best-structured register becomes a filing exercise.

5. Information and Communication

This component addresses how risk information flows through your organization. Who needs to know what? How quickly? Through which channels?

I test this through tabletop exercises where I tell the CEO to stay silent and let the team work through a crisis scenario.

The first time I ran this exercise, the scenario was a mass casualty incident. The team froze. They stumbled over what to do first and who should take the lead.

That’s CEO dependency revealing itself.

The questions I ask during these exercises surface problems that risk registers never capture:

Initial Response: When you get that alert, what’s the very first thing you do? How do you verify it’s real? Who is your backup if you’re unavailable?

Communication: Who in another department do you need to reach? How do you find their current contact information? How do you communicate if email is down?

Resources: What specific tools do you need and where are they? Do you have the necessary permissions? How do you access backup systems?

Operations: What manual workarounds do you rely on that aren’t documented? How do you handle sensitive data if systems are offline?

These tactical questions reveal operational friction before crisis hits.

The Six Risk Categories Every Nonprofit Must Address

The COSO framework provides structure, but nonprofits face specific risk exposures:

Financial risks include revenue concentration, cash flow volatility, and grant dependency. When your largest funder represents 40% of your budget, you don’t have financial stability. You have financial exposure.

Legal and regulatory risks span employment law, contracts, intellectual property, and sector-specific regulations. For public health nonprofits, this includes HIPAA. For educational organizations, FERPA. For any nonprofit, Form 990 compliance.

Operational risks cover everything from key person dependency to supply chain disruptions to facility issues. If your executive director leaving would create organizational chaos, you have an operational risk.

Technological risks have exploded in recent years. Yet 80% of nonprofits have no cybersecurity plan. They hold donor data, client information, and financial records with minimal protection.

Strategic risks emerge from mission drift, competitive positioning, and partnership decisions. The nonprofit that expands programs without capacity planning faces strategic risk.

Reputational risks can destroy decades of trust in hours. A data breach, financial scandal, or leadership failure can evaporate donor confidence instantly.

Black Swans vs. Gray Swans: The Distinction That Matters

Nassim Taleb defined Black Swan events with three characteristics: unpredictable, massive impact, and retrospectively rationalized as predictable.

True Black Swans lie outside regular expectations. Nothing in the past convincingly points to their possibility.

Gray Swans are different.

Dr. Deborah Pretty of Pentland Analytics calls them “unknown knowns”—anticipated, discussed, warned about with increasing urgency, but ignored. They’re predictable but unlikely surprises.

COVID-19 was a Gray Swan. Health organizations had been expecting a pandemic for years. Credible warnings existed. Preparation was possible. Yet most organizations were caught unprepared.

The risks keeping nonprofit leaders up at night aren’t the ones coming.

They worry about funding gaps. They should worry about ransomware attacks. They focus on donor retention. They should focus on operational dependencies. They stress about program metrics. They should stress about succession planning.

The most common reaction I get when discussing AI-enabled cyberattacks with nonprofit leaders is overwhelm mixed with powerlessness. They perceive cybersecurity as a technical problem for IT, not a strategic governance issue.

They cite limited budgets and expertise. They believe they’re too small to be targets. They focus on immediate funding needs over long-term operational threats.

This is the disconnect: organizational culture prioritizes immediate, mission-driven outcomes over long-term, complex operational risks, even when those risks pose existential threats.

Making the Framework Work in Resource-Constrained Environments

The 2017 COSO framework was designed for flexibility. A community nonprofit can apply the same principles as a major institution.

The difference is scale, not structure.

Start with governance. Get one board member genuinely interested in risk oversight. Make risk assessment a standing agenda item, not an annual presentation.

Integrate risk into strategy discussions. Before approving new programs, ask: What risks does this introduce? What’s our response plan?

Build a simple but living risk register. Assign clear ownership. Define escalation triggers. Review high-priority risks quarterly in operational meetings.

Run tabletop exercises starting with frontline staff. They know the operational realities, the workarounds, the hidden dependencies. Surface those gaps before bringing scenarios to leadership.

Focus on Gray Swans. The predictable threats you’re ignoring will cause more damage than the unpredictable ones you can’t control.

And remember: being right about risks doesn’t matter if you can’t convince people with power to act on them.

The 2017 COSO framework gave us the structure. The real work is making risk management a strategic conversation, not a compliance exercise.

That’s where most nonprofits still fail.

And that’s where the opportunity exists.